The country of Zimbabwe, led by Robert Mugabe, had once earned the praise of Western nations in the 1980’s. Now, the country is embroiled in all sorts of domestic maladies. The implementation of a disastrous land redistribution policy in 2000, which stripped white farmers of their property in a supposed favor of ownership by the black majority, would have profound negative effects on the economy. The collapse of the agricultural sector would lead to mass unemployment, a scarcity in the availability of food, and a rise in consumer commodity prices. These factors would cause nearly 3,500 Zimbabweans die every week from the combined effects of HIV/AIDS, poverty, and malnutrition. That number grows larger every day from a lack of fresh drinking water and persistent food shortages causing the average life expectancy in Zimbabwe to fall to under 40 years of age. Freedom of speech is outlawed, and to maintain their hold on power, the confiscators of the farms and Mugabe’s party, The Zimbabwe African National Union—Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) has been criticized for using violence and murder to intimidate opponents. At the root of Zimbabwe’s problems is a “corrupt political elite,” who are attempting to protect themselves from accountability for the “wholesale looting of Zimbabwe that followed the mismanaged land reform in 2000.” Having “behaved with utter impunity for…two decades, these elite are determined to hang on to power no matter what the consequences.”[1]

The country of Zimbabwe, led by Robert Mugabe, had once earned the praise of Western nations in the 1980’s. Now, the country is embroiled in all sorts of domestic maladies. The implementation of a disastrous land redistribution policy in 2000, which stripped white farmers of their property in a supposed favor of ownership by the black majority, would have profound negative effects on the economy. The collapse of the agricultural sector would lead to mass unemployment, a scarcity in the availability of food, and a rise in consumer commodity prices. These factors would cause nearly 3,500 Zimbabweans die every week from the combined effects of HIV/AIDS, poverty, and malnutrition. That number grows larger every day from a lack of fresh drinking water and persistent food shortages causing the average life expectancy in Zimbabwe to fall to under 40 years of age. Freedom of speech is outlawed, and to maintain their hold on power, the confiscators of the farms and Mugabe’s party, The Zimbabwe African National Union—Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) has been criticized for using violence and murder to intimidate opponents. At the root of Zimbabwe’s problems is a “corrupt political elite,” who are attempting to protect themselves from accountability for the “wholesale looting of Zimbabwe that followed the mismanaged land reform in 2000.” Having “behaved with utter impunity for…two decades, these elite are determined to hang on to power no matter what the consequences.”[1]

Economically valuable white-owned farms would become a politicized issue in 2000, by war veterans who supported Mugabe and ZANU-PF in the country’s independence movement. Considering the land “a just prize,” these war veterans “continued to clamor for the commercial farmland prior to the 2000 parliamentary election.” While Zimbabwe’s constitution outlawed the seizure of the farms without proper compensation[2], Mugabe and others fueled calls “to return the ‘stolen lands’ to black Zimbabweans.[3] The redistribution of land had previously occurred by legal means, with confidence in the courts and law enforcement. The country had “a secure rule of law, with a modern property rights system,” whereby owners were able to “use the equity in their land to develop and build new businesses, or expand their old ones.” This led to strong real GDP growth, which averaged 4.3 percent per year after independence. The system kept the food supply regular and employed about 350,000 black workers, while frequently providing money for local schools and clinics. The 2000 land redistribution was not the request of the general populace. A poll by the South Africa–based Helen Suzman Foundation in that same year, found that only 9 percent of Zimbabweans said land reform was the most important issue. Ordinary citizens supported the constitutional laws and in voter referendum in early 2000, “they rejected Mugabe’s attempt to broaden the state’s confiscatory powers.”[4]

In 2000, nearly 4,500 white families owned most of these large commercial farms, while 840,000 black farmers “eked out a living” on the communal lands, and Mugabe fought to remove this “legacy of colonialism.”[5] These communal lands “were typically plagued by tragedy-of-the-commons types of problems”, becoming overused and greatly eroded over time. Due to no clear property titles, “there was often squabbling over land use rights.” Commercial farms belonging to the whites “had secure property titles” and this stability “gave farmers large incentives to efficiently manage the land.”[6] Capital from banks to “loan funds for machinery, irrigation pipes, seeds, and tools” eased the burden of rapid population growth. [7] A large irrigation network was developed, giving Zimbabwe “a tremendous cushion against droughts.” The argument that the white farmers possessed all the best land is inaccurate. Although the communal lands could be drier in some areas, “many were directly adjacent to commercial farms or in high-rainfall areas,” while some commercial farms were in very arid parts of Zimbabwe. Blacks with land titles and plots of their own could be successful as well. Small-scale commercial farms, run by about 8,500 black farmers, had access to credit and were also productive. A stable balance had been achieved that maintained positive growth for the Zimbabwean economy.[8]

Upsetting this balance by removing and/or ignoring the laws set in the constitution regarding property rights would prove to be the undoing of the country’s agricultural sector, and ultimately, the Zimbabwean dollar. Advisors to Mugabe anticipated such, but went unheard. In a confidential memo from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, prior to the land reforms, the central bank predicted that the takeover of white-owned farms “would result in a pullout of foreign investment, defaults on farm bank loans, and a massive decline in agricultural production.” The seizures went forward, with the official goal being “to divide the farms into hundreds of thousands of small plots for traditional black farmers.” A majority of the farms, however, wound up as gifts for the war veterans and political supporters, whose lack of farming knowledge proved ruinous to the farm.[9] Within a few years, the economy “was shrinking faster than any other in the world, at 18 percent per year.” The Zimbabwean dollar (still far from its final worth), lost much of its value by heavy inflation. Foreign investors did indeed pull out of the country, and Zimbabwe lost much of its standing with the World Bank, with risk premium investment on loans to the country climbing from 4 to 20 percent. Domestically, there became “less collateral for bank loans” and banks, if they did not collapse outright, were hesitant in their extension of credit.

Commercial farming was crippled, losing nearly three-quarters of its value within a year. Economist Craig Richardson estimates a loss of “$5.3 billion—more than three and a half times the amount of all the foreign aid given by the World Bank to Zimbabwe since its independence.”[10] The loss, affecting the entire spectrum of the economy, forced hundreds of companies closed within one year of Mugabe’s implementation of the new land policies. From insufficient “equity in the banking system…Industrial production would decline “by 10.5 percent in 2001 and an estimated 17.5 percent in 2002.” The failure of commercial farming in Zimbabwe would send experienced farmers to other African countries, “taking with them their intricate knowledge of farming practices.” Meanwhile, the government blamed the ruined economy on “a variety of external factors, including Western conspiracies and racism.” Mugabe’s often used assertion of “continuous years of drought,” although partially factual, was not the cause, as reservoirs were “full throughout the economic downturn.” In some cases, “irrigation pipes (which are) no longer owned by anyone …are being dug up for scrap in a free-for-all. Some are even melted down to make coffin handles, one of the few growth industries left in the country,” with thousands dying weekly from the effects of malnutrition and cholera. [11] The inflation rate of the Zim dollar would rapidly increase, throwing the country into economic chaos.

SUNRISE

After five years of negative growth and paralyzing rise in prices, an attempt was made in August of 2006 to re-denominate the currency. Millions, sometimes billions, of Zim dollars were “needed for the simplest transactions.” An effort hailed as “Operation Sunshine” and accompanied by mass advertising and sloganeering, sought to remove a few zeros from the currency. The Governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ), Dr. Gideon Gono, spearheaded the campaign. Citizens were given 21 days to change “their money, computer systems, accounting and pricing.” Roadblocks, manned by the Youth Militia, loyal to ZANU-PF and Mugabe, were set up to “catch “unpatriotic” Zimbabweans who were carrying in excess of the legal limit of $100 million.” Those who “hoarded” money were advertised as the culprits of the monetary crisis. Banks were also instructed “seize sums deposited by individuals” in excess of that amount, and report the matter to the RBZ for investigation. [12] Inflation was declared “illegal,” after the rapid emergence of a black market, and for a four month period, anyone who raised prices or wages was threatened with arrest and punishment.[13] By lowering money demand, and “pressuring the money supply to increase, inflation became self perpetuating.[14]

In July of 2007, the government, trying to take the country’s financial woes out of the international spotlight, postponed the announcement of inflation figures. “It seems pretty obvious that the government sees no political sense in continuing to advertise its own failure to turn around the economy by releasing those astronomical inflation figures,” said an investment analyst with a leading Harare bank.[15] Days later, Mugabe asserted that more money would be created if necessary to fund municipal projects. Stating, “Where money for projects has not been found, we will print it,” ignoring historical evidence that just simply printing more money does not stop the demand on its value; oftentimes, it only fuels inflation. [16] He called for price cuts of nearly fifty percent, accusing store owners of profiteering from the inflation crisis. Businesses could no longer afford to sell their goods at the newly imposed rates, and the lower prices left shelves empty of food staples and other essentials. Nearly 5,000 shopkeepers who were not in compliance of the new laws were fined, arrested, or beaten.[17] Further devaluation of the currency in September led Zimbabwean Economist Rob Davies, to say “It’s an amazing admission by the government that it has done everything wrong.” Meanwhile, the black market rates of the Zim Dollar climbed to Z$30,000 to the US Dollar. “It’s too little, too late,” Mr. Davies said. “It is irrelevant…this is just going to encourage the black market and it will have no impact on reducing inflation.”[18]

In late 2007, Gono announced a new series of bills called Sunrise 2. Higher value Z$750,000, Z$500,000 and Z$250,000 bank notes would be introduced. “The cash shortages will be a thing of the past,” he said. “Within the next few days there will be sufficient cash to go about our business.” Individual bank deposits were limited to no more than Z$50 million. Any excess funds would be forfeited to the government. Bank deposits would be monitored by “government officials.” The publicized aim was to catch the profiteers of the inflation crisis. Gono blamed these “cash barons” for “hoarding cash for speculative purposes.”[19] They consisted of a large section of Zimbabwean elite, familiar to Gono. “I know three quarters of them but professional ethics do not allow me to name them by name. If challenged I will name them.” While these still unnamed “cash barons” were able to turn a handsome profit from inflation, the Zimbabwe dollar was becoming worthless. The new highest denomination could not even buy one loaf of the lowest quality bread, which at the time, sold for Z$800,000.[20]

Keeping up with the printing of currency would prove to be very difficult for Mugabe and the RBZ. “The regime is surviving by printing money,” said Martin Rupiya, professor of war and security studies at the University of Zimbabwe. “At this stage there is no other way.” An Austrian company supplying the banknotes, Giesecke & Devrient (G&D), was selling the Zimbabwe government blank sheets of bank notes at the rate of Z$170 trillion a week.[21] G&D would eventually bow to international pressure and cease their shipments,[22] leaving the state owned Fidelity Printers & Refiners in a crisis. Two-thirds of the workforce was placed on immediate leave. “If you think this currency shortage is bad, wait two weeks. By then it will be a disaster,” said a senior Fidelity staffer, who spoke anonymously to the Los Angeles Times. “The paper will run out in two weeks, he said. During the first half of 2007, the company had printed “100-million, 250-million and 500-million notes in rapid succession, all now practically worthless.” [23] “We have the world’s first million-dollar banana,” joked one woman shopper.[24] House prices and lottery prizes now see figures in the quadrillions of Z$. Estimates would expect quintillions soon after. Such long numbers required new software had to be written for machines and banking computers. The Zim Dollar had added so many zeros that the ATMs no longer worked.[25]

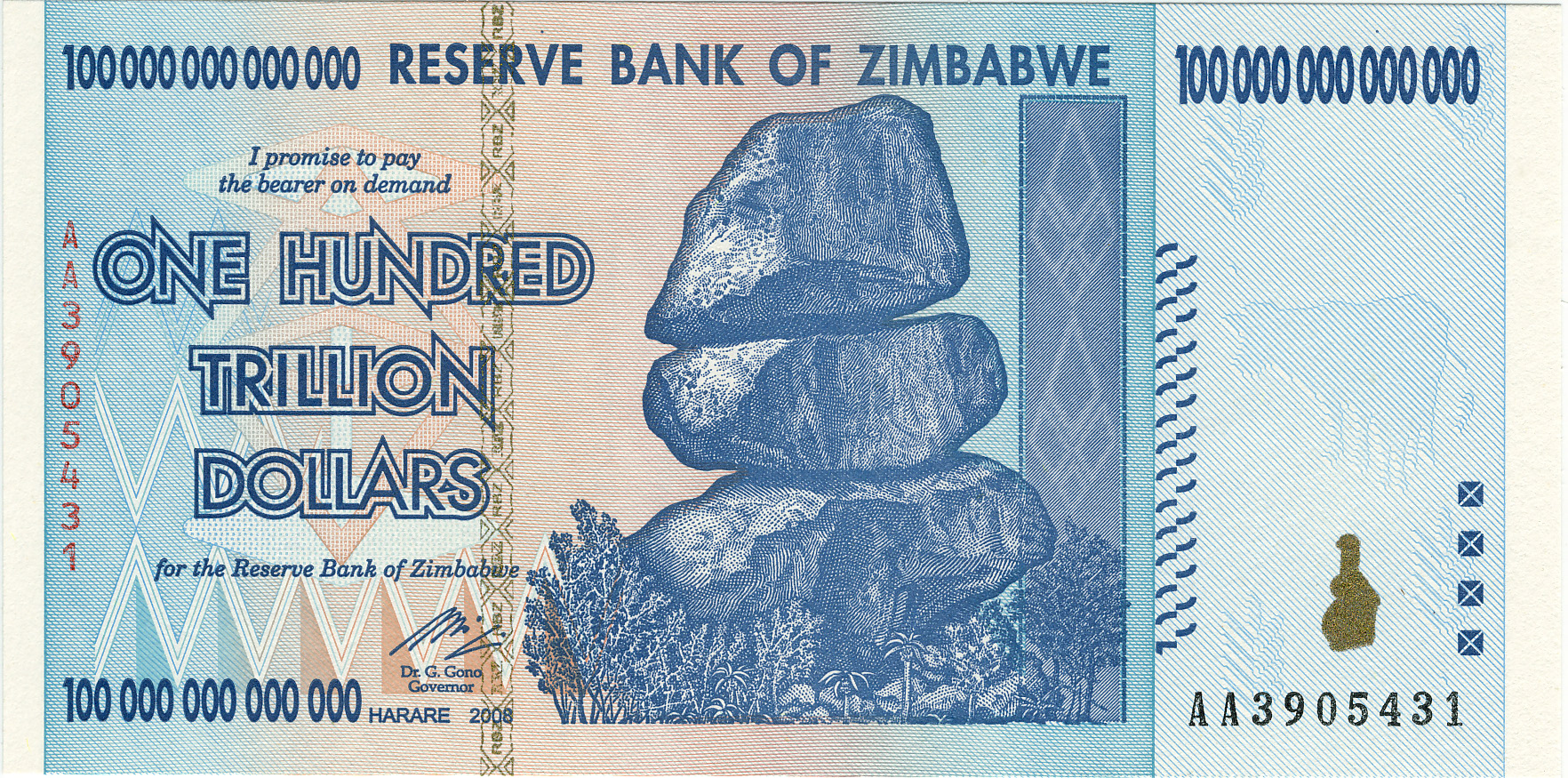

The RBZ would subtract ten of them in August of 2008, turning ten billion dollars into one revalued dollar.[26] It was not enough, the zeros would return. By January of 2009, acting finance minister, Patrick Chinamasa would issue a $50 billion note, worth only two loaves of bread. Weeks earlier, $10 billion dollars had bought twenty loaves. John Robertson, an economist in Zimbabwe could not see the sense of the $50 billion and $20 billion notes. ‘I am not really sure what these notes would be for,” he said. “No one now accepts the local currency. It is a waste of resources to print Zimbabwe dollar notes now. Who accepts a currency that loses value by almost 100 percent daily?” One rate of exchange on January 9th brought one US dollar for Z$25 billion. Inflation was estimated at 231 million percent and quickly rising.[27] A week later, the RBZ would issue a $100 trillion note.[28] By that point “grocery purchases, government hospital bills, property sales, rent, vegetables and even mobile phone recharge cards” were paid in foreign currency, mainly the SA Rand and US Dollar. For most “the worthless Zimbabwe dollar virtually ceases to be legal tender.”[29]

***

NEW LEADERSHIP &DOLLARIZATION

The change in the power structure of the country would have a positive effect on the economy. New Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) gained control of the Finance Minister position, relieving Chinamasa of his temporary position. Tendai Biti, the new minister, was tasked with the job of rebuilding the economy. In his revised 2009 budget to parliament, Biti noted that “indirect taxes made up of customs and excise duty have contributed 88 percent of government revenue, which means that the government has been literally sustained by beer and cigarettes.” “This is unacceptable,” the minister added. Biti gave bleaker revenue projections than Chinamasa, a Mugabe appointee. The country would only make about $1 billion, with a discrepancy of nearly $700 million from when quoted early.[30] Realizing that the Zim Dollar was no longer in use, he lifted all restrictions on foreign currencies and committed to tying the economy to dollarization. “The death of the Zimbabwe dollar is a reality we have to live with. Since October 2008 our national currency has become moribund,” Biti said. “In this regard, I therefore announce the removal of all foreign currency surrender requirements.”[31]

Economist Steve Hanke[32], a proponent of dollarization, believes that of all monetary systems that Zimbabwe has implemented, “Central banking is the only system that worked badly,” that “To retain central banking is to perpetuate a system that has destroyed the livelihoods of millions of Zimbabweans.” By conducting business using stable foreign money, all demand for the Zim dollar will cease, the hyperinflation will dissipate, and prices can be reestablished. Hanke suggests that a path towards dollarization and currency boards, which have long stood as fixes for hyperinflation, would help balance the economy. “Any one of these systems, or a combination of them, could be implemented immediately, without preconditions, and would therefore quickly put an end to hyperinflation and produce stable money. It is time for Zimbabwe to adopt one of these proven monetary systems and discard its failed experiment with central banking.” Hanke takes the position that the printing of money was a failure, and that “the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe shall cease to issue Zimbabwe dollars.” [33] The worthlessness of the Zim Dollar would finally make printing an unviable option. Dollarization had already replaced the currency without any formal decree. The market made an attempt to fix itself.

In his address announcing the Short-Term Emergency Recovery Programme (STERP), Mugabe “wished to appeal to all those countries which wish us to succeed to support our national endeavor to turn around our economy. “So I, on behalf of the inclusive Government and the people of Zimbabwe, say: ‘Friends of Zimbabwe please come to our aid’.”[34] For the aid that the country needs, Mugabe would need to adhere to a series of World Bank demands. The fund suspended Zimbabwe in June 2003, following the initial inflation when the government fell behind on debt repayments.[35] For the country to be eligible for aid, a reversal of Mugabe’s land policy is necessary, as well as an “intensification of (the) process of democratization.” Foreign investment must be attracted to “promote participation of the private sector, and the country must work to “improve policies to support agriculture, rural development, and food security.[36] “Technical and financial assistance from the IMF will depend on establishing a track record of sound policy implementation, donor support and a resolution of overdue financial obligations to official creditors, including the IMF,” the International Monetary Fund said, following an announcement by the government of a 3 percent drop in prices.[37] Minister Biti said STERP was “motivated by the need to get the economy back on track as quickly as possible,” when announcing his plan to implement these request “We need to take Zimbabwe out of the current rut and move it forward.” Mugabe would add that “STERP … will enable us as a nation to direct our energies and resources to exclusively developmental issues affecting the lives of our people,”[38]

As these new strategies begin to rescue the economy, there is hope that with the coalition government, more progressive domestic policy will occur. Mugabe has held the spotlight during the crisis, and his (as well as ZANU-PF)’s failures increasingly become known to the world. Gideon Gono admitted on April 20, 2009 that he took hard currency from the bank accounts of private businesses and aid groups without permission, saying he was “trying to keep his country’s cash-strapped ministries running.” $7.3 million that could be accounted for was returned to the Global Fund, after threats to cut aid. He has also been accused of bribery, by offering cars to fifty new lawmakers, so that they could “preach” the message of economic reform. In all, he stood over the subtraction of 25 zeros, and is sharply criticized for the printing of more money without ample assets or reserves.[39] The Government elite “cash barons” who had profited from preferential rates on foreign currency can no longer do following the demise of the Zim Dollar. The new government is “working hard to separate Mr. Gono and Mr. Mugabe from their traditional control of the money and the Zimbabwean economy. “The process of change is irreversible,” said John Robertson, an independent economist in Harare. “The wedge will be driven harder and harder.” The new government has “eliminated or reduced a host of taxes and retail license fees that were previously funneled to the central bank.” Western governments continue keep international spotlight on Gono, criticizing him as the “personal paymaster to Mr. Mugabe himself.” The Zim dollar that their failed policies would create would find new life as novelty item. Street hawkers “have finally found a use for the worthless 100-trillion-dollar banknotes that were issued in January. They sell the bizarre banknotes as souvenirs to foreign tourists for US$2 each.” Just two months after the latest notes were printed, “’the currency with the never-ending string of zeroes is quickly fading into history.’”[40]

Bibliography

Beckerman, Paul. The Economics Of High Inflation. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992. 49

BBC. “Zimbabwe Rolls Out Z$100tr Note” January 16, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7832601.stm

Chanda, Never. “Zimbabwe Central Bank Unveils Higher Denominated Notes” Zim Online, December 20, 2007. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/dec20_2007.html#Z1

Chizhanie, Hendricks. “Harare Suspends Release Of Inflation Data” Zim Online, July 14, 2007. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/jul15_2007.html#Z1

CNN. “Zimbabwe Introduces $ 50 Billion Note” January 10, 2009. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/africa/01/10/zimbawe.currency/

CNN. “Zimbabwe ‘surviving on beer and cigarettes’” March 18, 2009. http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/africa/03/18/zimbabwe.finance/index.html

Coltart, David. “A Decade Of Suffering In Zimbabwe: Economic Collapse and Political Repression under Robert Mugabe” Cato Institute No. 5 (March 24, 2008): 2.

Dzirutwe, MacDonald. “Zimbabwe Introduces Higher Denomination Banknotes” Reuters, December 19, 2007. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/dec20_2007.html#Z1

Gordon, April A., Gordon Donald L. Understanding Contemporary Africa. 4th ed. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2007. 147

Hill, Geoff. The Battle for Zimbabwe. Cape Town: Zebra, 2003.: 102

Hanke, Steve. “Kill Central Bank to Fix Inflation in Zimbabwe” The Times, July 13, 2008. http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/kill-central-bank-fix-inflation-zimbabwe

Herald Sun. “$100 Billion for Three Eggs” July 24, 2008.

http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/billion-for-three-eggs/story-e6frf7jo-1111117008950

Herald, The. “Zimbabwe: New Economic Plan Launched” The Government of Zimbabwe. March 20, 2009. http://allafrica.com/stories/200903200007.html (subscription)

International Herald Tribune. “Mugabe Says Will Print More Money If There Isn’t Enough” The Associated Press, July 28, 2008. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/jul29_2007.html#Z1

Lamb, Christina. “Planeloads Of Cash Prop Up Mugabe” The Sunday Times, March 2, 2008. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/mar2a_2008.html#Z1

Los Angeles Times. “Lack Of Bank Note Paper Threatens Zimbabwe Economy” July 14, 2008.

Mafara, Wayne. “Mugabe Says Might Declare Emergency Over Prices” Zim Online, July 30, 2008. http://www.zimonline.co.za/Article.aspx?ArticleId=3487

Milton Friedman (1956), “The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by Friedman. Reprinted in The Optimum Quantity of Money (2005), pp. 51-67.

Raath, Jan. “Devaluation is ‘too little, too late’ to save Zimbabwe” The Times, September 7, 2007. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/archive/news/harare-devalues-dollar-but-too-little-too-late/story-e6frg6uf-1111114368949

Reuters. “Giesecke & Devrient Halts Deliveries to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe” July 1, 2008. http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS194545+01-Jul-2008+PRN20080701

Richardson, Craig, “How the Loss of Property Rights Caused Zimbabwe’s Collapse” Economic Development Bulletin. Cato Institute no. 4 (November 14, 2005)

Sadik, Nafis. Population Policies And Programmes: Lessons Learned From Two Decades Of Experience. New York: New York University Press, 1991. Annex Table 2 :400

Shaw, Angus. “Zimbabwe admits raiding private bank accounts” Associated Press, April 20, 2009.

Sokwanele. “Welcome to a New Sunrise in Zimbabwe.” August 29, 2006. http://www.sokwanele.com/thisiszimbabwe/archives/427

Wines, Michael. “As Inflation Soars, Zimbabwe Economy Plunges” New York Times, February 7, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/07/world/africa/07zimbabwe.html?ex=1328504400&en=5709ec03b6b62b0d&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss

York, Geoffrey. “How Zimbabwe Slew The Dragon Of Hyperinflation” The Zimbabwean, March 23, 2009. http://www.thezimbabwean.co/news/19871/how-zimbabwe-slew-the-dragon-of-hyperinflation.html

Zimbabwe Independent. “Revised Budget Dashes Infrastructure Repair Hopes” March 19, 2009. http://www.theindependent.co.zw/2009/03/19/revised-budget-dashes-infrastructure-repair-hopes/

‘Zero to Hero’ advertising campaign accompanying “Operation Sunrise”

http://www.flickr.com/photos/sokwanele/228321814/

Released on January 16, 2009, the 100 trillion dollar note was worth about US$33 on the black market

http://lee.org/blog/2009/04/09/100-trillion-dollars

Zim Dollars find value as cheap advertisments. April 1, 2009

http://www.woostercollective.com/2009/04/thanks_to_mugabe.html

[1] Coltart, David. “A Decade Of Suffering In Zimbabwe: Economic Collapse and Political Repression under Robert Mugabe” Cato Institute No. 5 (March 24, 2008): 2.

[2] Richardson, Craig, “How the Loss of Property Rights Caused Zimbabwe’s Collapse” Economic Development Bulletin. Cato Institute no. 4 (November 14, 2005)

[3] Hill, Geoff. The Battle for Zimbabwe. Cape Town: Zebra, 2003.: 102

[4] Richardson

[5] Hill: 102

[6] Richardson

[7] Sadik, Nafis. Population Policies And Programmes: Lessons Learned From Two Decades Of Experience. New York: New York University Press, 1991. Annex Table 2 :400

[8] Richardson

[9] Hill, Geoff. The Battle for Zimbabwe. Cape Town: Zebra, 2003: 110

[10] Craig J. Richardson is associate professor of economics at Salem College and author of The Collapse of Zimbabwe in the Wake of the 2000-2003 Land Reforms (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 2004).

[11] Richardson

[12] Sokwanele. “Welcome to a New Sunrise in Zimbabwe.” August 29, 2006 http://www.sokwanele.com/thisiszimbabwe/archives/427

[13] Wines, Michael. “As Inflation Soars, Zimbabwe Economy Plunges” New York Times, February 7, 2007.

[14] Beckerman, Paul. The Economics Of High Inflation. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992. 49

[15] Chizhanie, Hendricks. “Harare Suspends Release Of Inflation Data” Zim Online, July 14, 2007. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/jul15_2007.html#Z1

[16] Milton Friedman (1956), “The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by M. Friedman. Reprinted in The Optimum Quantity of Money (2005), pp. 51-67.

[17]International Herald Tribune. “Mugabe Says Will Print More Money If There Isn’t Enough” The Associated Press, July 28, 2008.

[18] Raath, Jan. “Devaluation is ‘too little, too late’ to save Zimbabwe” The Times, September 7, 2007. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/archive/news/harare-devalues-dollar-but-too-little-too-late/story-e6frg6uf-1111114368949

[19] Dzirutwe, MacDonald. “Zimbabwe Introduces Higher Denomination Banknotes” Reuters, December 19, 2007.

[20] Chanda, Never. “Zimbabwe Central Bank Unveils Higher Denominated Notes” Zim Online, December 20, 2007. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/dec20_2007.html#Z1

[21] Lamb, Christina. “Planeloads Of Cash Prop Up Mugabe” The Sunday Times, March 2, 2008.

[22] Reuters. “Giesecke & Devrient Halts Deliveries to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe” July 1, 2008. http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS194545+01-Jul-2008+PRN20080701

[23] Los Angeles Times. “Lack Of Bank Note Paper Threatens Zimbabwe Economy” July 14, 2008.

[24] Lamb.

[25] Herald Sun. “$100 Billion For Three Eggs” July 24, 2008.

http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/billion-for-three-eggs/story-e6frf7jo-1111117008950

[26] Mafara, Wayne. “Mugabe Says Might Declare Emergency Over Prices” Zim Online, July 30, 2008.

[27] CNN. “Zimbabwe Introduces $ 50 Billion Note” January 10, 2009. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/africa/01/10/zimbawe.currency/

[28] BBC. “Zimbabwe Rolls Out Z$100tr Note” January 16, 2009.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7832601.stm

[29] CNN. “Zimbabwe Introduces $ 50 Billion Note” January 10, 2009.

[30] CNN. “Zimbabwe ‘surviving on beer and cigarettes’” March 18, 2009. http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/africa/03/18/zimbabwe.finance/index.html

[31] Zimbabwe Independent. “Revised Budget Dashes Infrastructure Repair Hopes” March 19, 2009. http://www.theindependent.co.zw/2009/03/19/revised-budget-dashes-infrastructure-repair-hopes/

[32] Steve H. Hanke is a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and a senior fellow at the Cato Institute.

[33] Hanke, Steve. “Kill Central Bank to Fix Inflation in Zimbabwe” The Times, July 13, 2008. http://www.thetimes.co.za/Business/BusinessTimes/Article1.aspx?id=800444

[34] Herald, The. “Zimbabwe: New Economic Plan Launched” The Government of Zimbabwe. March 20, 2009.

[35] BBC. “Zimbabwe prices begin to fall” March 25, 2009.

[36] Gordon, April A., Gordon Donald L. Understanding Contemporary Africa. 4th ed. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2007. 147

[37] BBC. “Zimbabwe prices begin to fall”

[38] Herald, The. “Zimbabwe: New Economic Plan Launched”

[39] Shaw, Angus. “Zimbabwe admits raiding private bank accounts” Associated Press, April 20, 2009.

[40] York, Geoffrey. “How Zimbabwe Slew The Dragon Of Hyperinflation” The Zimbabwean, March 23, 2009. http://www.thezimbabwean.co/news/19871/how-zimbabwe-slew-the-dragon-of-hyperinflation.html